The following is a guest post by Mark Pyzyk, who recently received his Ph.D. from the Classics Department, and who served as co-curator on the Classics @ 125 exhibit:

This year, Stanford Classics turns 125, and to celebrate, we have put together an exhibit examining its early history. While small and undistinguished early on, the department quickly produced scholars of distinction. Today it is a major center of American classics, and a world leader in the study of ancient Greece and Rome. Still, the century and a quarter that intervenes between us and its foundation is often a sort of ever-advancing black box—that is, we seldom have an institutional memory that extends any further back than the recollection of the faculty's most senior member. Earlier outlines of the department's history are therefore simply lost. This exhibit hopes to shed some light on that earlier place and time.

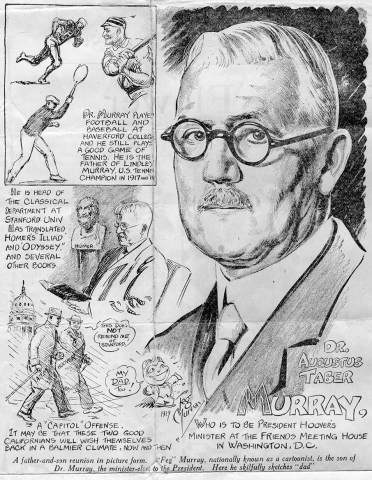

To that end, one finds small treasures in the Stanford University Archives, especially in the personal papers of early faculty. Take, for instance, someone like Augustus Taber Murray. He was among the department's first professors. A scholar of Greek literature, he produced major translations of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey (as well as the Private Orations of Demosthenes)—those who have used the Loeb Classical editions of either will have come across them. He was also a sporting man, and contributed to Stanford's early athletic culture, championing the amateurism of the 19th-century gentleman and condemning specialized athletics. As chairman of the Athletics Committee, for instance, he confidently pronounced that, "(intercollegiate football) with its professional coaches, its elaborate machinery, its secret signals... its building of teams rather than training of men––has been banished from Stanford athletics for all time to come" (Stanford Alumnus, April 1916). It was a poor prediction, obviously, but tells us something about the link between virtue and athletics—along with the prizing of process over results—in his time.

[David Jordan's All-Starrs] (SC1071). A.T. Murray, top-left. David Starr Jordan, bottom-center. Courtesy of the Stanford University Archives.

But Murray was perhaps even more important as a religious and political figure (though he would surely deny the latter—I assert it, nevertheless). As a member of the San Jose chapter of the Society of Friends, he was a major figure in Bay Area Quakerism. It was in this connection that he became friends with Herbert Hoover, who—when he was elected president in 1928—asked his former professor (Hoover had been a member of the first graduating class of Stanford) to come with him and serve as spiritual advisor to the president. This Murray did, and they were reportedly very close in Washington. To the extent that Quakerism influenced Hoover's progressive ideas, as well as his suspicion of government intervention in particular problems of economic life (Smith, G.S. "Herbert Hoover", in Religion in the Oval Office. 2015), Murray the Quaker stood as a figure of some political influence.

Dr. Murray Goes to Washington (SC0221). Comic drawn by his son, Feg, who became a prominent sports-cartoonist, Published in The Christian Herald, 2/2/1929. Courtesy of the Stanford University Archives.

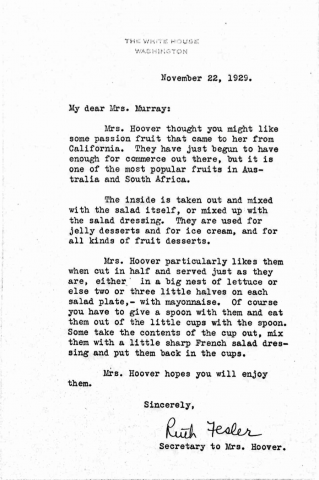

The personal friendship of Murray and Hoover emerges in dozens of documents exchanged, which can be found in the Stanford University Archives, as well as the Hoover Archive. We see it in letters about the loss of family, and in reminiscences about religious retreats and their days on the Farm. Occasionally it takes on smaller and stranger forms, for instance the sharing of recipes for fruit salad. Lou Henry Hoover's preference for serving passion fruit with mayonnaise is just one more oddity that reinforces a sense of displacement and alienation from that earlier age!

A Gift of Passion Fruit (67033). Courtesy of the Hoover Presidential Library.

For other such journeying into the past of Stanford Classics, please join us in the south lobby of Green Library. The exhibition, Classics @ 125, will be on display through the summer. It makes use of materials from the Stanford University Archives and the Stanford University Archaeology Collections. Questions and comments about this exhibit can be directed to pyzykm@alumni.stanford.edu.

The Stanford University Libraries’ Department of Special Collections and University Archives acquires, preserves, and provides access to primary source materials that support the research needs of the Stanford community and beyond, including through the creation of exhibits.

For more information about any of the collection materials included in this exhibit, please contact the University Archives at universityarchives@stanford.edu.

Stanford University Home

Stanford University Home